Medical Image Augmentation & Synthetic Data

Reducing Data Dependency · Part 2

As discussed in the Data Bottleneck article, medical imaging AI faces structural constraints: massive storage and transfer requirements, high annotation costs, strict ethical and regulatory limitations, and generally limited data availability, especially in areas like rare diseases.

In the previous post, we explored alternatives such as unsupervised, self-supervised, and semi-supervised learning, showing how models can learn effectively from fewer labels.

At its core, the goal is simple: turn limited medical data into richer, more diverse training resources without requiring more patient data.

Another powerful strategy for reducing data dependency is to generate additional data artificially. This includes both data augmentation, which transforms existing images, and synthetic data generation, which creates entirely new ones. These approaches help improve model generalisation, robustness, and overall performance when real-world data is scarce.

Data Augmentation

What is data augmentation?

Data augmentation is the process of generating additional training samples by transforming existing images. Numerous studies show that it improves model performance on independent, unseen data, and it is now a standard practice in medical AI development.

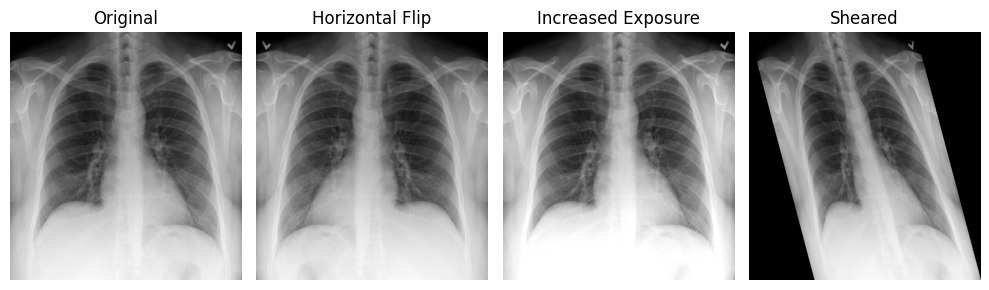

According to , commonly used augmentation techniques fall into two main groups:

Classical augmentations

- Rotation

- Flipping (mirroring)

- Translation: shifting the image along one or more axes

- Scaling: zooming in or out

- Shearing: sliding one image edge while keeping the opposite edge fixed

- Intensity augmentation: modifying pixel values (e.g., blurring, sharpening, brightness/contrast adjustments, histogram equalization, normalization)

- Color modification (RGB images): histogram manipulation, channel isolation, hue/saturation/value adjustments, or swapping color spaces.

GAN-based augmentations (advanced)

- Conditional GAN (cGAN): extends the GAN framework by providing the generator and discriminator with additional information (e.g., class labels or alternative modalities) to guide image synthesis.

- Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN): uses convolutional layers in both the generator and discriminator, enabling more stable training and higher-quality images compared with early GANs.

- Cycle GAN: performs image-to-image translation without paired training, converting images from one domain to another (e.g., CT → MRI, low-dose → high-dose).

- Wasserstein GAN (WGAN): optimises an approximation of the Wasserstein-1 distance (Earth Mover’s Distance) to improve stability, reduce mode collapse, and provide meaningful learning curves for tuning and debugging.

- Style GAN: introduces a style-based generator architecture that separates high-level structure from fine detail, allowing more intuitive control over image synthesis.

- Progressively trained GAN (ProGAN): grows both networks by gradually increasing image resolution, resulting in faster, more stable training and higher-quality outputs.

When does augmentation bring value?

Data augmentation is especially valuable in medical imaging in the following scenarios:

- When datasets are small or imbalanced Medical imaging data is often limited (e.g., rare diseases, privacy restrictions). Augmentation increases sample diversity and helps models generalize beyond the available cases.

- When real-world variability needs to be simulated Augmentation is highly effective when it mimics realistic differences across scanners, acquisition protocols, patient anatomy, or imaging conditions. Clinically plausible transformations consistently improve robustness and cross-site generalization.

- When annotations are limited or costly Because expert labeling is expensive and time-consuming, augmentation helps models learn more effectively from fewer annotated samples, reducing the dependency on large labeled datasets.

A note on labels

Classical augmentations (rotations, flips, intensity changes, etc.) preserve the link between images and labels because the same transformation is applied to both the image and its annotation (e.g., segmentation masks).

In contrast, GAN-based augmentations usually do not generate corresponding labels, since the images are synthesized from scratch rather than derived from an already labeled sample.

Limitations and common mistakes

- Limitations:

- Unrealistic transformations: Large rotations, incorrect flips, extreme deformations, or aggressive intensity changes can produce anatomically implausible images, which confuse rather than help the model.

- Synthetic images without labels: GAN-based augmentations generate new images but do not produce matching labels, limiting their use for tasks that require masks, contours, or bounding boxes.

- Poor-quality or misleading images: Augmentations may distort anatomy or introduce artefacts. Without proper quality control, these images can teach the model incorrect patterns.

- Common mistakes:

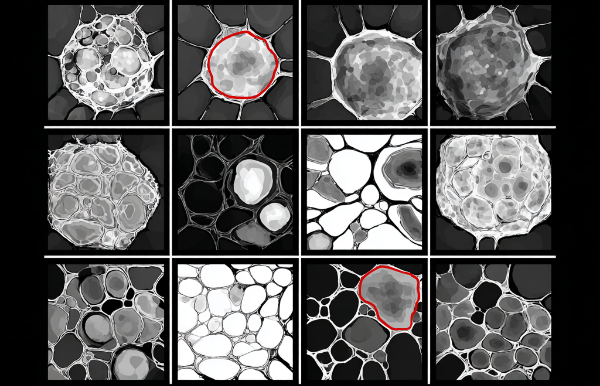

- Breaking the link between images and labels For segmentation or detection, images and labels must undergo the exact same transformation. Even small misalignments degrade performance.

- Skipping quality checks on GAN-generated images: Synthetic images may contain artifacts, blurriness, missing anatomy, or fake pathology. If integrated blindly, the model may learn these errors instead of real clinical features.

- Assuming “more augmentation” is always better: Excessive or overly aggressive augmentations can push images away from the true clinical distribution, harming model performance and introducing bias.

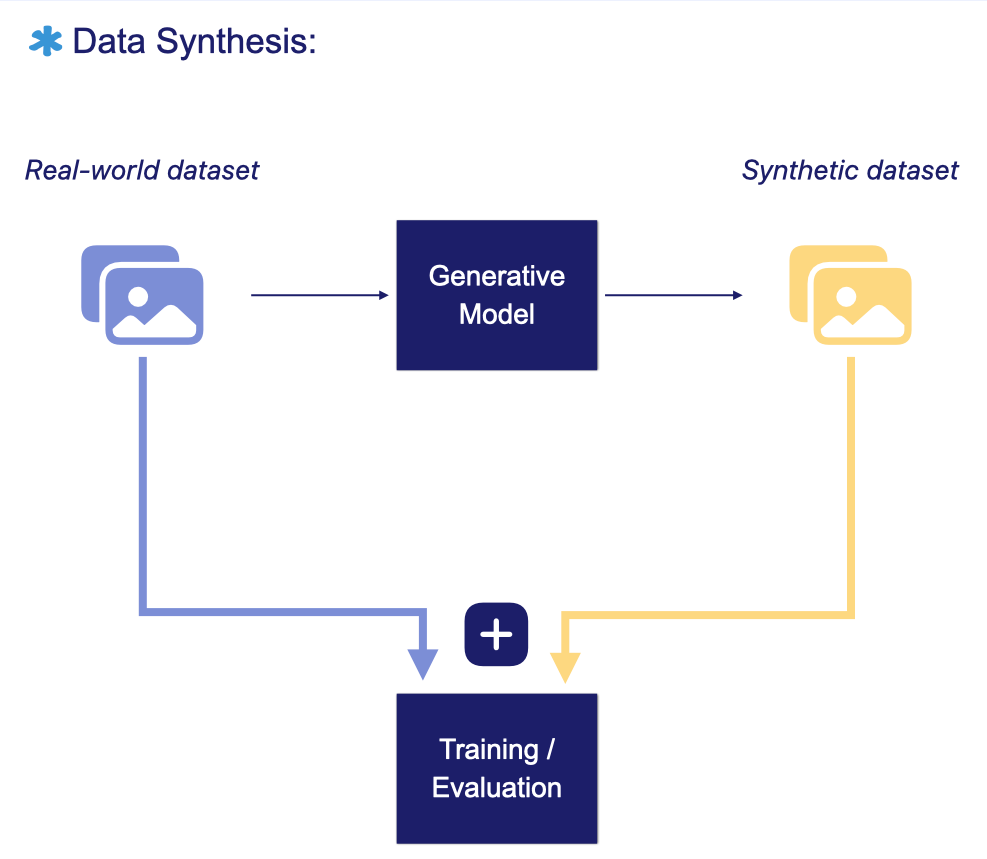

Data Synthesis

Synthetic data has been explored as an alternative source of training data for AI models. Instead of relying solely on real-world samples, these datasets are artificially generated, through simulations or generative AI models, to mimic the distribution, variability, and structural relationships found in real data.

In medical imaging, generative models have been used to create synthetic samples across several domains, including brain MRI, retinal fundus photography, and digital pathology.

For synthetic images to be clinically useful, they should replicate real patient data so faithfully that even experienced radiologists cannot reliably distinguish synthetic scans from real ones.

AI Models for medical image synthesis

- Diffusion models begin with pure noise and progressively refine it through a reverse Markov process. Each step moves the sample closer to a coherent image that reflects the patterns learned from the training data.

- Generative Adversarial Networks , or GANs, consist of a generator that creates synthetic images from a latent space and a discriminator that assesses whether they appear real. Through adversarial training, the generator becomes better at producing realistic images while the discriminator becomes more accurate at distinguishing real from synthetic.

- Variational autoencoders encode an image into a latent representation and then reconstruct it back to its original form. Training improves this reconstruction by minimising the variational lower bound, which measures the difference between the original image and its reconstruction.

When does data synthesis bring value?

In medical imaging, synthetic datasets have been used to :

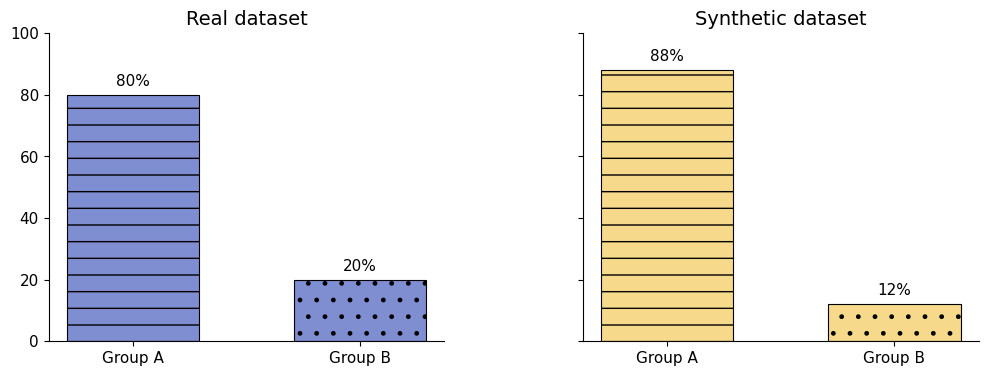

- Expand or balance training data when datasets are small or imbalanced. Models often show reduced sensitivity for rare diseases, and demographic imbalances (for example ethnicity or sex) can introduce fairness issues, as performance typically drops on underrepresented groups.

- Enable privacy-preserving data sharing, since the generated images can represent fictitious patients rather than real individuals.

- Translate images across modalities, which can support clinical interpretation, for example by creating synthetic MRI from CT for pre-operative localisation of a tumour.

- Translate images across domains to reduce variability introduced by different scanners, acquisition protocols, or institutions, improving domain adaptation.

- Generate synthetic contrast-enhanced scans from low-dose or non-contrast images. This may reduce the reliance on multiple imaging protocols and lower the contrast agent dose without compromising diagnostic quality. In turn, it can reduce patient risk, cut costs, and help manage contrast media shortages.

- Support model interpretability by helping reveal which features a model is using and whether these are clinically expected. This improves understanding of the reasoning behind model predictions.

- Create training scenarios for radiologists, including rare pathologies or unusual anatomical variations, broadening exposure without requiring additional real cases.

Risks and limitations

- Bias

- Synthetic images can inherit or even amplify biases (demographic, gender, etc.) present in the training data.

- Although it can help rebalance underrepresented groups, it may also produce overgeneralised or unrealistic patterns.

- Rigorous evaluation of generated images is essential to minimise bias.

- Distribution drift

- Synthetic data reflects the distribution of the dataset used to generate it. If clinical practice, imaging protocols, or patient populations evolve, the synthetic images may become outdated and no longer representative of current real-world conditions.

- Incorrect mixing of real and synthetic data

- If synthetic and real images are combined without proper balancing, preprocessing alignment, or quality control, models may learn to distinguish the data sources instead of the clinical features.

- This can degrade performance and introduce unintended biases.

- Limited assessment metrics:

- Synthetic images must be non-identifiable, high quality, and diverse, yet evaluating all these aspects is challenging and no single metric captures every failure mode.

- Common metrics such as the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) or Inception Score (IS) provide only broad, dataset-level evaluations and cannot assess individual images.

- Downstream task performance (e.g., classification or segmentation accuracy) is often a more practical indicator of usefulness.

- Newer metrics such as α-precision, β-recall, authenticity, and global consistency aim to detect specific issues at the level of single images, but they remain underused in medical imaging.

- Privacy leakage:

- Generative models do not fully guarantee privacy. For example, deepfakes could mimic real patients by fabricating clinical findings or be misused to support fraudulent medical billing.

- To guarantee traceability, accountability, privacy, health care organisations should maintain a clear data lifecycle, with documentation and safeguards such as encryption, authentication, access control, regular audits, and secure data disposal.

- Dependability of synthetic medical images:

- Hallucinations occur when fictitious anatomical structures appear or when real anatomy is missing.

- Images with unrealistic features are generally unusable and can lead to erroneous model predictions.

- Quality checks are essential to ensure that synthetic images do not contain artefacts.

- Regulatory concerns:

- Regulators are unlikely to accept synthetic datasets for validation or testing, since they may not accurately represent real-world variability and distribution.

- Synthetic datasets should be used carefully and always alongside real clinical data.

Conclusion

Data augmentation and synthetic data are powerful tools for reducing data dependency in medical imaging. When applied correctly, they can improve robustness, expand training diversity, support privacy-preserving workflows, and strengthen model interpretability.

At the same time, these techniques must be used responsibly. Synthetic datasets come with their own risks, including hidden biases, privacy leakage, distribution drift and regulatory uncertainty. The most successful organisations treat augmentation and synthesis not as shortcuts but as controlled, well-validated components of a broader data strategy grounded in real clinical data.